Social Proof: Science, Psychology and Application. With Examples

Social Proof is a social and psychological phenomenon, also known as “informational social influence,” where individuals copy other people’s behaviour. It is responsible for the “buzz” that follows success and the way popularity comes in waves.

The effect occurs when a person is unsure of the correct way to behave. In this situation, they will often look to others for clues about the correct behaviour. The same principle applies when someone is unsure whether to trust something or believe someone. Social Proof can even shape our preferences and the choices we make.

The Science, Psychology and Application of Social Proof

Whether you know it or not, major decisions in your life have been influenced by Social Proof. Similarly, if you have ever wondered what makes a song become a “hit”, why companies stand or fall on a star rating, or why some bad products outsell their rivals, Social Proof is the answer.

Thanks to digital technologies such as Social Media, which connect us to a vast global community, the influence of Social Proof extends further than at any other time in history. This article explores how it works, the science behind it and the way it affects our lives.

How Does Social Proof Work

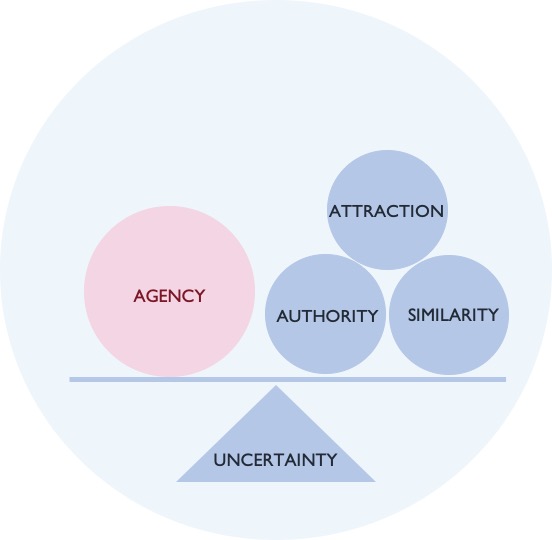

What other people say, think and do is one of the most powerful motivators we experience. Acceptance is a significant “Intrinsic Motivation,” so we often choose conformity rather than following our own direction. This is exacerbated by the fact that we almost always assume that other people possess more knowledge of a given situation than we do. A number factors are know to increase the effect of group persuasion:

The Multiple Source Effect

People give more authority to ideas that are stated by a number of sources. The Multiple Source effect makes the use of review sections in eCommerce websites particularly effective.

Uncertainty

The effect of Social Proof is enhanced significantly when ambiguity is introduced. For example, when a consumer is trying a new type of product for the first time, they will be more persuaded by majority opinion. Additionally, the influence of consensus is maximised when it is applied before the consumer has tried a product. In this case, the information derived from Social Proof creates an Anchoring effect.

Similarity

The effect of Social Proof is increased when an individual believes they share something in common with the people they are observing. During an experiment on the use of laughter tracks for television footage, subjects displayed more enjoyment of a clip when they believed the laughter track was taken from an audience they identified with.

Attraction

We take our cue from the people around us, and none more than the people we admire. The Halo effect occurs when a particularly important or glamorous person transfers positive associations to the world around them. This effect extends to an individual’s ability to inform our decisions.

The Authority Principle

The influence of authority over perceptions of “normal” behaviour has been explored in depth. Authority can be experienced in a number of ways, and it has a significant impact on the effect of Social Proof. Endorsements from experts or celebrities enhance the experience of group persuasion, especially when the subject identifies with those authority figures.

Robert Cialdini and the Science of Social Proof

The influence of groups over individual behaviour has been studied since the 1930s. In 1935 the social psychologist Muzafer Sherif identified a remarkable difference in perception between individuals exposed to group influence and those separate from it. When subjects were exposed to the influence of peers, estimations for things like the speed of a moving dot were significantly altered.

In 1969, the sales and marketing expert Cavett Robert published Human Engineering and Motivation. In a section where Robert imagined selling to a “Mr Jones”, he famously stated:

95 % of people are imitators and only 5% initiators…people are persuaded more by the actions of others than by any proof we can offer.

The term “Social Proof” was first coined by Robert Cialdini in his 1984 book Influence. It was one of his six Principles of Persuasion:

- Reciprocity

- Commitment and Consistency

- Authority

- Liking

- Scarcity

- Conformity (Social Proof)

In his book, Cialdini noted the peculiar popularity of laughter tracks with television executives, despite their apparent unpopularity with audiences. He also noted the strange universality of the boast that a product was selling well. Since scarcity and uniqueness add value to a product, this boast seemed misplaced. In both cases, Cialdini was able to demonstrate the influence of group persuasion through experiment.

Most people are instinctively sceptical of this statement. Surely, we all have our own personal preferences? However, two recent studies suggest that our preferences are less personal than they seem…

Since the formalisation of Social Proof as a phenomenon, further research has explored the influence of social and cultural factors over the phenomenon. A meta-analysis published in the Psychological Bulletin in 1996, for example, highlighted the difference in the way group persuasion affects collectivist and individualist societies.

Examples of Social Proof

Cialdini notes a few common examples of the use of Social Proof in commercial settings.

- During the disco era, club owners would often allow lines to grow unnecessarily long outside their clubs. Although there was lots of room inside, the club owners knew that the line would attract more customers.

- Charity workers who display a long list of previous donors to prospective subscribers are more likely to receive a donation. This effect is enhanced when the potential donor knows people on the list.

There are countless other examples that affect everyday life. For example:

- Politicians frequently emphasise the popularity of their campaigns and overstate their winning margins (even when it is obviously a lie).

- People who are unemployed for long periods find it harder to get jobs than the recently unemployed.

- An industry of artificially manufactured “ghost followers” has developed for businesses looking to suggest Social Media popularity.

- Tourists often perform “traditional” rituals that cause major problems. In 2014, tourists collapsed part of a bridge in central Paris after generations of couples attached locks to the railings. Similarly, a petrified forest in Arizona was infamously destroyed after a sign asking tourists not to remove fossilised trees started a trend.

Social Proof and “Self-Fulfilling Prophecies”

Mathew Salganik is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Princeton. In 2008, he conducted an experiment to test the effect that Social Proof would have on personal preference. Salganik created an artificial sharing platform for music. Whilst the songs were real, he introduced his own (invented) popularity rankings.

Some of the songs, which were not highly rated elsewhere, were given inflated popularity. One or two of the least popular songs were even displayed as the most popular. Remarkably, he found that the songs with artificially enhanced popularity became his participants’ favourites. In his summary, Salganik concluded that:

…most songs experienced self-fulilling prophecies, in which perceived—but initially false—popularity became real over time…

How Social Proof Could Save the World: Cialdini and Goldstein

In an another experiment, the “fathers of persuasion” Robert Cialdini and Noah Goldstein attempted to study whether Social Proof could be used to encourage environmentally friendly behaviour in hotels. Their task was to persuade guests to reuse their towels.

The experiment provided a sample of hotel guests (B – Social Proof) with signs informing them that the majority of other guests in the hotel had chosen to reuse their towels.

Join your fellow guests in helping to save the environment – (B)

Another sample (A – Industry Standard) were given a sign requesting that they reuse towels on environmental grounds.

Help save the environment by reusing your towels – (A)

Group A (who received the industry standard environmental message) recycled their towels 35.1% of the time. Remarkably, the group exposed to the Social Proof message (B) recycled their towels 44.1% of the time. This experiment, and others like it, has led to serious discussions among policy makers about the ethics and efficacy of using cognitive biases and psychological influence to guide behaviour.

Conclusion

For more detail on the factors that enhance Social Proof, or to see more examples of it being applied, visit our post on Social Proof Marketing. To explore other cognitive effects that shape our lives, browse our library of Consumer Behaviour articles, or follow our list of 13 must-read Neuromarketing Books.

Social proof is really a powerful technique. Many companies use this to their advantage with shopper claims like “no 1 in the world”, “trusted by homemakers”, etc.

For the past few years I’ve been trying something which I call anti-social proof. For example, at parties I’m usually able to get to the bar faster just by avoiding the crowds. Many times while boarding a flight I’ve used the less-popular escalator/queue and saved a lot of time and hassle.

“Anti-social Proof” sounds interesting – if you have any more examples, I’d be fascinated!